- Home

- Jim Proser

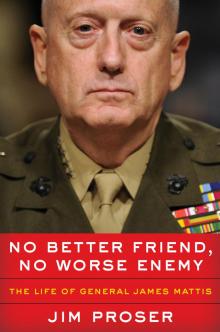

No Better Friend, No Worse Enemy

No Better Friend, No Worse Enemy Read online

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Introduction

1: No Better Friend

2: No Worse Enemy

3: Liberation

4: Beyond Baghdad

5: A Girl Named Alice

6: The Enemy of My Enemy

7: Task Force Ripper

8: The Sleeping Enemy

9: Graveyard of Empires

10: City of Mosques

Epilogue: No Better Friend, No Worse Enemy

Acknowledgments

Notes

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

James N. Mattis was the first Trump presidential cabinet nominee. His nomination received nearly unanimous bipartisan congressional support, with only one dissenting vote. He secured a rare waiver of the guidelines that exclude recently active military leaders from the position of secretary of defense.1 What could create such unprecedented unity, even enthusiasm, in the hyperpartisan political rancor of 2017?

No doubt the urgency of accomplishing a quick, smooth transition of military leadership was in play, but what were the other reasons behind this easy consensus? Beyond Mattis’s obvious military competence for the position on paper, what were the qualities of character, the much-reported personal magnetism, that created such universal confidence? These qualities are the primary focus of this book. With the awesome power of America’s arsenal now under his command, we would be prudent to ask: Who is this man, underneath his general’s stars?

We should ask how this humble and deeply thoughtful man has walked the path of mortal combat with the most barbaric evil of our time, Islamic terrorism. How is it possible that he has defeated the most bloodthirsty dictators and terrorists with insight, humor, fighting courage, and fierce compassion, not only for his fellow Marines but for the innocent victims of war? Fortunately many eyewitness accounts provide clues to these questions. We might look, for instance, to his lighthearted encouragement to his beloved Marines just before launching the Iraq invasion of Operation Iraqi Freedom, “Fight with a happy heart and strong spirit.”2 Or to his emotional warning to Sunni civilian tribal leaders during the Anbar Awakening in Iraq: “I come in peace. I didn’t bring artillery. But I’m pleading with you, with tears in my eyes. Fuck with me and I’ll kill you all.”3

The martial and personal values examined here have earned Jim Mattis the trust of America’s political leaders. But why should we, the people who must pay the price of freedom with our lives, trust this man? May you find the answer to that question here, in the words and deeds of a visionary warrior.

1

No Better Friend

General Krulak said, when he was commandant of the Marine Corps, every year starting about a week before Christmas he and his wife would bake hundreds and hundreds of Christmas cookies. They would package them in small bundles. Then on Christmas day, he would load his vehicle and drive to every Marine guard post in the Washington-Annapolis-Baltimore area to deliver a small package of Christmas cookies to Marines pulling guard duty that day.

One year, he had gone down to Quantico as one of his stops. He went to the command center and gave a package to the lance corporal on duty. He asked, “Who’s the officer of the day?”

The lance corporal said, “Sir, it’s Brigadier General Mattis.”

And General Krulak said, “No, no, no. I know who General Mattis is. I mean, who’s the officer of the day today, Christmas day?”

The lance corporal, feeling a little anxious, said, “Sir, it is Brigadier General Mattis.”

General Krulak said that he spotted in the back room a cot, or a daybed. He said, “No, Lance Corporal. Who slept in that bed last night?”

The lance corporal said, “Sir, it was Brigadier General Mattis.”

About that time, General Krulak said that General Mattis came in, in a duty uniform with a sword, and General Krulak said, “Jim, what are you doing here on Christmas day? Why do you have duty?”

General Mattis told him that the young officer who was scheduled to have duty had a family, and General Mattis decided it was better for the young officer to spend Christmas Day with his family, and so he chose to have duty on Christmas Day.

—Dr. Albert C. Pierce, the director of the Center for the Study of Professional Military Ethics at the US Naval Academy, introducing General Mattis at the academy

0800 Hours—23 April 2003—Camp Commando, Kuwait

In a large, nondescript military tent, fifty-three-year-old Major General James Mattis, small and lean, with a reputation as a ferocious and brilliant warrior, briefs hundreds of his fellow US Marines. With him is Major General James Amos, who’s in charge of the Third Marine Air Wing of Mattis’s overall command, the First Marine Division. The division is geared up to invade Iraq, just thirty-five miles north, launching Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Mattis, a gentlemanly ladies’ man but a lifelong bachelor, has dedicated his life completely to the success and safety of the warriors he commands. In return, he is deeply beloved by them. His constant study of history and philosophy has earned him the affectionate nickname the Warrior Monk and made being smart and well-read cool, elevating the sometimes anti-intellectual, tribal Marine culture. He ordered every Marine in the First Division to read Russell Braddon’s The Siege, which follows the ill-fated British Expeditionary Force during World War I in what was then called Mesopotamia. Mattis wants every Marine to understand the inhospitable Iraqi terrain and the mistakes that cost the British twenty-five thousand men.

His voice is calm and loud, with a slight sibilance that softens some of his s’s. He speaks without notes, hands on hips or in “knife-hand” gestures, fixing his attention on individual Marines as he scans the rows of officers from the front to the back of the room. Marine commanders sit in rows before him now, Third Air Wing pilots up front in tan flight suits, pistols strapped across their chests, ground commanders behind them in desert camouflage. They are silent, intent on every word. Among the commanders is Lieutenant Colonel Stanton Coerr, who later reports on this meeting, “Gentlemen, this is going to be the most air-centric division in the history of warfare,” Mattis says. “Don’t you worry about the lack of shaping; if we need to kill something, it is going to get killed. I would storm the gates of Hell if Third Marine Air Wing was overhead.”1

By shaping, he means shaping of the battlefield by air power and artillery. This is usually the preparation for battle meant to find and exploit the enemy’s weakest spot. But instead of shaping, Mattis’s new “maneuver warfare” relies on speed and mobility, as he then makes clear with typical good humor.

“There is one way to have a short but exciting conversation with me,” he continues, “and that is to move too slow. Gentlemen, this is not a marathon, this is a sprint. In about a month, I am going to go forward of our Marines up to the border between Iraq and Kuwait. And when I get there, one of two things is going to happen. Either the commander of the Fifty-First Mechanized [Iraqi] Division is going to surrender his army in the field to me, or he and all his guys are going to die.”2

Maps are flashed up, showing the initial battlespace coordination line, and the Marines are given their rules of engagement—they are permitted to kill anything beyond that line that appears to be a threat. But in the summer of 2002, when Mattis assumed command of the First Marine Division, he warned the division staff of several realities. According to one of his public affairs officers, Captain Joe Plenzler, he said, “Iraq has a population of 33 million people, and we sure as hell don’t want to fight all of them. We only want to fight the ones that are working to keep Saddam Hussein in power.”3 He goes on to i

nsist that if the Iraqis they encountered wanted to help, or just to stand aside, they should find no better friend than a US Marine.

This phrase, “no better friend than a US Marine,” came from Mattis’s reading of Roman general Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who once remarked, “No friend ever served me, and no enemy ever wronged me, whom I have not repaid in full.”4 When he took command of the First Division in 2000, Mattis fashioned Sulla’s quote into the division’s now famous motto, “No better friend, no worse enemy.”5

* * *

The second part of the briefing takes place in the open desert inside a bulldozed arena where the Marines and their coalition allies walk through the first five days of the coming battle on a scale replica of the battlefield representing the 345 miles of Iraqi terrain between the Kuwaiti border and Baghdad. Nearly the size of a football field, the sculpted topography includes every road, canal, village, and oil field that the fast-moving attack forces will encounter. Canals and rivers are filled with blue sand, and oil fields are marked with black pyramids representing oil derricks.

Mattis grabs a microphone and, again without notes, explains through a loudspeaker what each unit will do and in what sequence this will occur, emphasizing coordination but rejecting synchronization. No one is to wait, everyone is to advance. Constantly and quickly advance. Their mission is to capture Baghdad, not to get bogged down in firefights in every village.

Next to the gray-haired Mattis stands his surprising lead intelligence analyst, taking it all in. Twenty-year-old Lance Corporal Nathan Osowski is some kind of savant. He knows the Iraqi order of battle—the number and location of forces—better than anyone in the division. Osowski can recall the most intricate details, like the number and kinds of armor in different Iraqi units, on demand, and now he adds the battlefield details before him into his mental database. Mattis, who has always recognized and valued talent over rank, keeps Osowski in his inner circle of advisers, among the majors and generals.

Representatives of each unit wear football jerseys in specific colors, with unit-identifying numbers on their backs. As Mattis describes each advance, the representatives walk to their proper places on the terrain model. About three hundred officers stand and sit on the dune above the battlefield, watching Mattis’s battle plan in action. This is a textbook demonstration of “maneuver warfare,”6 which sliced through Iraq’s defenses in one hundred hours during Operation Desert Storm twelve years earlier. Mattis specifies every objective for every unit at the end of every day for the first five days of the war, an impressive display of study and preparation.

At the end of this rehearsal of concept, questions are answered and Mattis dismisses the group. Mike Murdoch, one of the British company commanders, leans over to Lieutenant Colonel Coerr and asks, “Mate, are all your generals that good?”7

1900 Hours—20 March 2003—Camp Matilda on the Kuwait-Iraq Border

The seven-meter-high earthen berm marking the border between Kuwait and Iraq erupts from the high explosive charges placed by the combat engineers of the First Marine Expeditionary Force, often referred to as I MEF. Fine, chalky dust from the blast drifts down in the night breeze onto the growing traffic jam that will eventually grow to seventy-five thousand American and coalition invaders and their tens of thousands of trucks, amtracs (heavy trucks with tank treads instead of wheels), light armored vehicles (LAVs)—small, fast, tank-like vehicles—Jeep-sized Humvees, and gigantic M1A1 Abrams tanks.

Lieutenant Nathaniel “Nate” Fick, who served under General Mattis in Afghanistan two years earlier just after 9/11, assembles his platoon in the dusty, barren invasion staging area at Camp Matilda. He knows the vital importance Mattis places on every Marine understanding his commander’s intent, and so he reads the general’s “Message to All Hands” to his men:

For decades, Saddam Hussein has tortured, imprisoned, raped and murdered the Iraqi people; invaded neighboring countries without provocation; and threatened the world with weapons of mass destruction.

The time has come to end his reign of terror. On your young shoulders rest the hopes of mankind. When I give you the word, together we will cross the Line of Departure, close with those forces that choose to fight, and destroy them. Our fight is not with the Iraqi people, nor is it with members of the Iraqi army who choose to surrender. While we will move swiftly and aggressively against those who resist, we will treat all others with decency, demonstrating chivalry and soldierly compassion for people who have endured a lifetime under Saddam’s oppression. Chemical attack, treachery, and use of the innocent as human shields can be expected, as can other unethical tactics.

Take it all in stride. Be the hunter, not the hunted: never allow your unit to be caught with its guard down. Use good judgment and act in the best interests of our nation. You are part of the world’s most feared and trusted force. Engage your brain before you engage your weapon. Share your courage with each other as we enter the uncertain terrain north of the Line of Departure. Keep faith in your comrades on your left and right and Marine Air overhead. Fight with a happy heart and strong spirit.

For the mission’s sake, our country’s sake, and the sake of the men who carried the Division’s colors in past battles—who fought for life and never lost their nerve—carry out your mission and keep your honor clean. Demonstrate to the world that there is “No Better Friend, No Worse Enemy” than a US Marine.8

* * *

In the futuristic-looking I MEF geodesic dome command post referred to as the Bug, crammed with computers, TV screens, communication radios, topographical models, and stacks of MRE boxes, Marine intelligence has hacked into the email account of the Iraqi general in command of forces near the border. Mattis emails the general, urging him to surrender, but the Iraqis continue to fire artillery intermittently and ineffectively toward I MEF positions. The Iraqi general doesn’t reply to Mattis’s emails. Earlier, Iraqi soldiers were observed by the border, laying more mines. Mattis has always hated mines, a fear that developed in his first days as a Marine over thirty-five years ago and has never left him. Their faceless, robotic nature may represent an unpredictable element to a student of human nature in warfare like Mattis. The new intel on the mines only adds to his growing disgust with the elusive and cowardly Iraqi commander. “I’m going to try one more time to save these fuckers’ lives,” he says.9

But he tries many times over the next two hours to appeal to his opposing general. He threatens him, begs him, appeals to him as an Iraqi patriot and family man, to save his own life and the lives of his men. The coalition invasion force is piling up and now stretches over eighteen miles back from the border, waiting for Mattis to give the order. But he tries and tries and tries again. If he doesn’t give the invasion order soon, some of the last units through the berm will be transiting at dawn, putting them in danger from Iraqi artillery. Finally, after hours of receiving only inconclusive, delaying replies but no surrender, Mattis gives up on the general and launches the invasion.

The traffic at the border is now snarled as vehicles attempt to jockey toward their assigned breaches in the berm. In the American vehicles, four to five Marines, most around nineteen years old, are itching to “get some,” to fire their weapons in combat, many for the first time. In the passenger seat of his overloaded Humvee, Lieutenant Fick waits in the dark with the four Marines of First Reconnaissance Battalion (First Recon), Bravo Company, Second Platoon. Mattis’s battle plan designates the 347 Marines of First Recon, including Alpha, Bravo, and Charlie Companies, as one of the three spearheads of the invasion. Fick’s second platoon will lead First Recon, at the very tip of the invasion’s center spearhead.

First Recon’s mission is to seize a remote bridge over the Euphrates at Nasariyah. Many may think this fairly routine mission might be their entire contribution to the war, but no one is sure what Saddam will throw at them on the way, now that the Marines were coming for him personally. Everyone expects chemical weapons attacks.

Evan Wright, a journalist embedded with Bra

vo Company, First Platoon, in the Humvee rolling directly in front of Fick, writes:

The point of Mattis’s plan to send First Recon ahead of his main battle forces is that this battalion will be among the fastest on the battlefield. As beat-up as First Recon’s Humvees are, they are quicker than tanks and, due to their small numbers, they can outmaneuver large concentrations of enemy forces. According to the doctrine of maneuver warfare, their relative speed, not their meager firepower, is their primary weapon. True to his radio call sign, Chaos, Mattis will use First Recon as his main agent for causing disorder on the battlefield by sending the Recon Marines into places where no one is expecting them.10

Once First Recon clears the breach at the border, they are to race 120 miles north to the Euphrates bridge. Their biggest concern is that they will be operating alone, isolated from the US Army and other Marine units that include thousands of troops, armored vehicles, and heavy artillery. In Humvees with little or no armor and supply trucks, they will trek through open desert that, somewhere, holds fifty thousand Iraqi troops equipped with more than a thousand tanks and other heavy armor.

US Marines and British forces will be in a race to secure the oil facilities and ports around Rumaylah, Basra, and Umm Qasr, forty-four miles east of the border. Mattis knows Saddam will set these oil facilities on fire if given time, as he did in the Gulf War in 1991, creating an environmental disaster. Coalition forces are tasked to secure the oil fields within forty-eight hours of crossing the border.

Mattis signals his aide-de-camp, twenty-two-year-old Lieutenant Warren Cook, to approach him. He tells Cook to saddle up the jump, they’re heading to Basra. Cook notifies the twenty-one members of the “jump platoon,” Mattis’s personal squad and mobile command post, to man their five lightly armored vehicles. Chaos, Mattis’s personal call sign, a code name that identifies him in radio communications, is on the move.

No Better Friend, No Worse Enemy

No Better Friend, No Worse Enemy